ASU 2018-12 spelled out a new methodology for calculating reserves for life insurance products. Kenji had worked many months to calculate the Liability for Future Policy Benefits (LFPB). He was exhausted. Yet, he was relieved. Cohorts were set up. The models were working as anticipated. Best estimate assumptions were in place. He had completed extensive single cell testing in Excel. The new roll forward reserve calculations allowed him to compute the reserves either retrospectively or prospectively. The roll forwards served as an excellent way to check the validity of the calculations. He was ready for a break. He handed over the initial reserves to the finance area. It was a time for a celebration with friends.

The celebration was short lived. The finance team called. They had placed the newly computed LFPB reserves into the overall financials. The results looked good, perhaps too good. Profits were very positive. The finance team was convinced a mistake had been made. No one in life insurance was supposed to have large profits now. Extra death claims due to COVID-19 had decimated results for the last year. Yet now, with the newly calculated reserves, profits appear to be good.

Kenji was tasked with figuring out what had gone wrong.

Some Basic Mechanics

ASU 2018-12 is also known as LDTI (Long Duration Targeted Improvements). It is applicable for insurance companies that report under US GAAP. LDTI made some major changes on how to compute reserves for traditional life products, such as term and whole life. These reserves are known as LFPB.

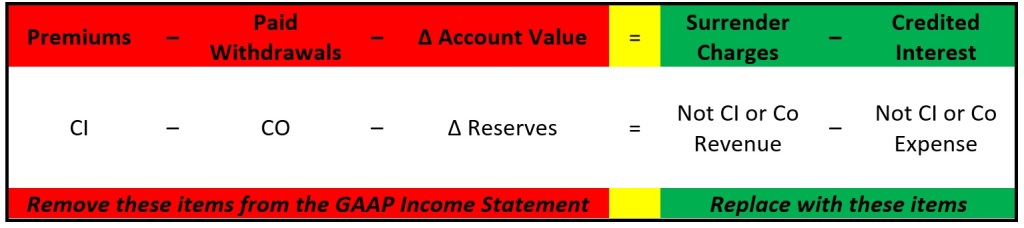

The basic formula for the change in LFPB for the current reporting period is:

Actual Premiums * Net Premium Ratio (NPR)

+ Interest Accrual on LFPB

– Actual Benefits

+ True Up Impact

Before LDTI, nearly no one had ever seen a simple formula for a change in a reserve. It was a mystery. But it was no longer a mystery. The change in LFPB, often one of the most important items on an income statement, is relatively simple. It works like as savings account. A portion of actual premiums are added into the LFPB each period. Actual benefits are paid out of the LFPB. Interest accrues to the LFPB. It begins at zero at policy issue, and it ends at zero after all the benefits have been paid.

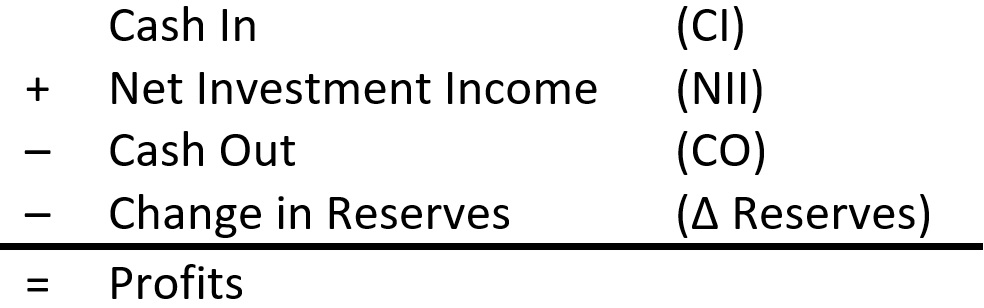

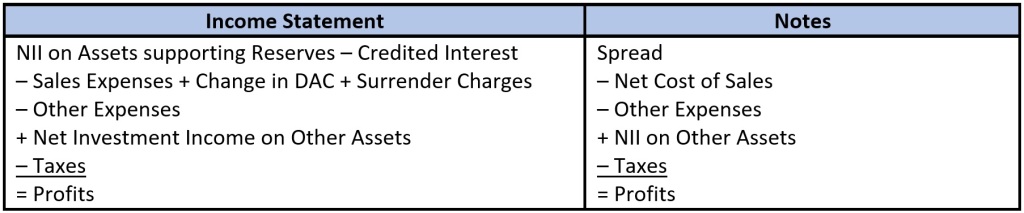

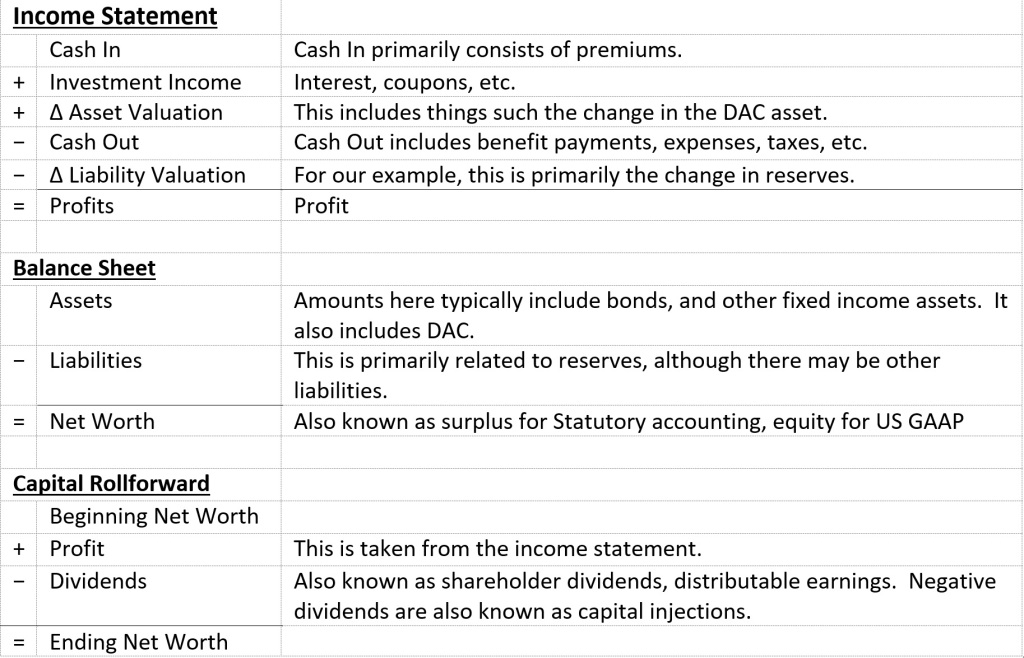

What do profits look like?

Normal Profit is:

Premiums

+ Investment Income

– Claims

– Change in Reserves

– Expenses

– Taxes

If we replace the “Change in Reserves” with the “Change in LFPB” we get:

Premiums * (1 – NPR)

+ (Investment Income – Interest Accrual on LFPB)

– True Up Impacts

– Expenses

– Taxes

Skip to the next section now if you are not really interested in all of the boring details.

The calculation is completed at the cohort level. Cohorts are groups of policies defined by product type and issue year.

The NPR (Net Premium Ratio) is the amount applied to the Present Value of Gross Premiums to make Present Value of Net Premiums equal to the Present Value of Benefits as of the start date of the cohort. Best estimate assumptions are utilized.

Cohorts will normally begin when policies are issued. However, for many companies, cohorts will begin as of 1/1/2021, if they were issued before this date. This is referred to as the modified retrospective approach. Many companies will not have enough data to do the calculations based on the original issue date. There will be more on this topic later.

For each reporting period, normally a quarter, the NPR is recalculated. It is always calculated over the life of the cohort. After each quarter, for the present value calculation, one quarter’s worth of expected results is replaced with one quarter of actual results. This has the impact of increasing or decreasing the NPR as needed.

If reality matches expectations, then the NPR never changes for a given cohort. If things are better than expected, then the NPR goes down. If things are worse, the NPR goes up.

Of course, there was one mystery element. It was for the “true up impacts”. This amount goes by many names. This includes items like “Effect of changes in cash flow assumptions,” and “Effect of actual variances from expected experience.” These are adjustments related to actual experience on mortality, morbidity and lapses not matching up to the assumptions used in the calculations.

If you do not have enough boring details yet, read ASU 2018-12 (FASB Org Link to ASU 2018-12).

When is it a good time for a pandemic?

The answer of course is never. But if there is going to be a pandemic, it is best that it happens when ASU 2018-12 is being implemented. Actual claims, even COVID-19 claims, are paid from the reserve. The drop in the reserve offsets the actual claims being paid, producing no profit/loss impact. Actual claims drop out of the equation from the previous section.

Wait a second! This cannot be true. OK, there is a profit/loss impact. It is very muted, at least for now. The reserving mechanism spreads excess claims (or smaller than expected claims) over the life of each cohort. Since most companies will have their cohorts starting as of 1/1/2021, most COVID claims will be spread out into the future.

No one wants a pandemic, but if there is a pandemic, LDTI could not have come at a better time.

But wait, there’s more!

So, LDTI has helped out with COVID claims. Yet, the profit levels still seemed too high. Kenji couldn’t help thinking about this. Then it hit him. The transition rules were producing steady streams of profit.

Under a true LFPB calculation, one needs the history of premiums and claims for all policies since the day they were sold. Tracing back all of this information can be a daunting task, as some policies in force were sold 50 or more years ago. So LDTI allows the modified retrospective method.

Under the modified retrospective method, one chooses a transition date. For most companies this will be 1/1/2021. The LFPB reserves, on a best estimate basis, are floored at the prior reserve amounts. The prior reserves had margins built in. Under LDTI, these margins are released as a constant percentage of premiums.

The NPR for old cohorts will be low in order to release more profit. For some old cohorts, it is even possible for the NPR to be negative.

Under the old methods the margins would have been released when policyholders surrender or die. However, this can be a long way off. The LFPB rules allow for much quicker release of margins.

Disclosures

LDTI requires public disclosures showing the details on the change in reserves. What was once an actuarial thing would soon become something anyone could figure out. Well perhaps not just anyone. Investor Analysts could certainly figure it out.

Investor Analysts would soon be able to make much better predictions about the change in reserves. Afterall, the details were there. Things seemed relatively straight forward. Then again, Investor Analysts tend to ask a lot of questions. Kenji knew that any amount in the “true-up impact” section of the “change in reserve” disclosure would require explanation. If things were worse than expected, Investor Analysts would want assumptions changed to strengthen reserves. If things were better than expected, they would want assumptions changed so that profits could be released. After assumption changes were made, it would be easier to predict profits.

It looked as if Investor Analysts would allow no relief. Then again, they had never allowed relief in the past. This was their job.

So, this was good?

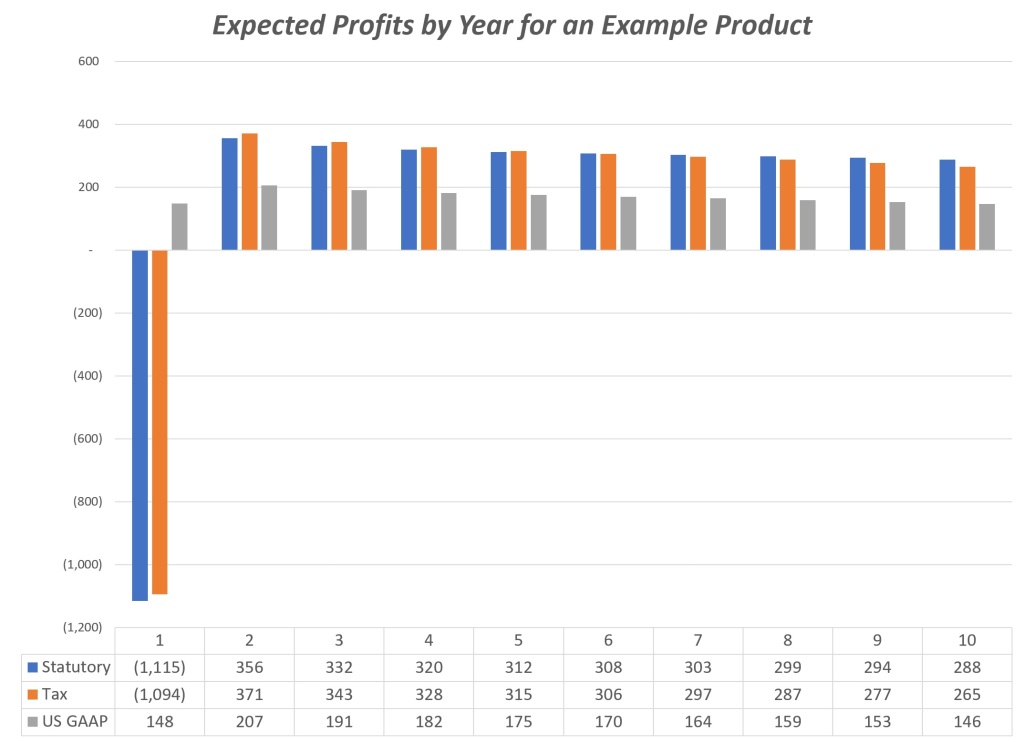

Kenji had figured out a few major items. Perhaps it was time to celebrate. Perhaps not. Yes, there was more profit now. That’s a good thing, isn’t it? The flip side is that there would be fewer profits in the future. This was especially true for policies sold after 1/1/2021, which would not have any margin in reserves. Sooner or later, this would need to be explained.

Kenji had taken the job in traditional life valuation simply because it was steady and predictable. He could see this would no longer be the case.

Kenji had never worried about assumption changes. Under the old rules, assumptions were set at the time the policies were sold, and then never changed. He used to simply walk over to the pricing area, get their assumptions, add some margins, and then forget about it thereafter. Afterall, changes to assumptions were not generally allowed in the past. Under LDTI, assumptions must be reviewed. If reality was not matching up to the current assumptions, he knew that the Investor Analysts would hound Senior Management, who in return would hound him.

Kenji had never worried about parts of the income statement, other than the “change in reserves”. This would no longer be the case. The change in reserves would be related to both actual claims and the size of actual premiums. The interest accrual on LFPB would be compared to net investment income.

So, Kenji was exhausted. Yet he was excited. His job would soon become less boring.